Paracelsus' Wisdom on the Ecosystem of Spirits

Western Magic is often distinguished into strands of high and low magic, learned and folk magic. Such and similar differentiations mainly centre on human social backgrounds as well as correlated motives of action and practice. I.e. they are rooted in an anthropological understanding of magic and how it is leveraged to make sense and alter the world. Unfortunately, with such seemingly obvious approach a lot of damage is already done. And mostly such damage has gone unnoticed and turned into thoroughly embedded bias in our Western tradition.

By centring on a human worldview and agenda, we inherently fail to give equal importance, value and explorative space to the rest of the (spirit) ecosystem of which man forms but a tiny part of. An introduction to magic, explored and explained from a more holistic perspective, could not pivot on human motives, but would need to begin at the precise opposite end: It would need to introduce us to the functions, forces and fields of living consciousness that exist around us - and which all hold their own motives and agendas.

Luckily for us, and yet sadly forgotten by most, Paracelsus (1493-1541) has done precisely that. And it took him less than two pages to set out the essential foundations of an ecosystem of spirits. In the following, I am sharing a few introductory remarks and observations to this short gem of a text, and then provide my own English translation as well as a modernized German one.

LVX,

Frater Acher

May the serpent bite its tail.

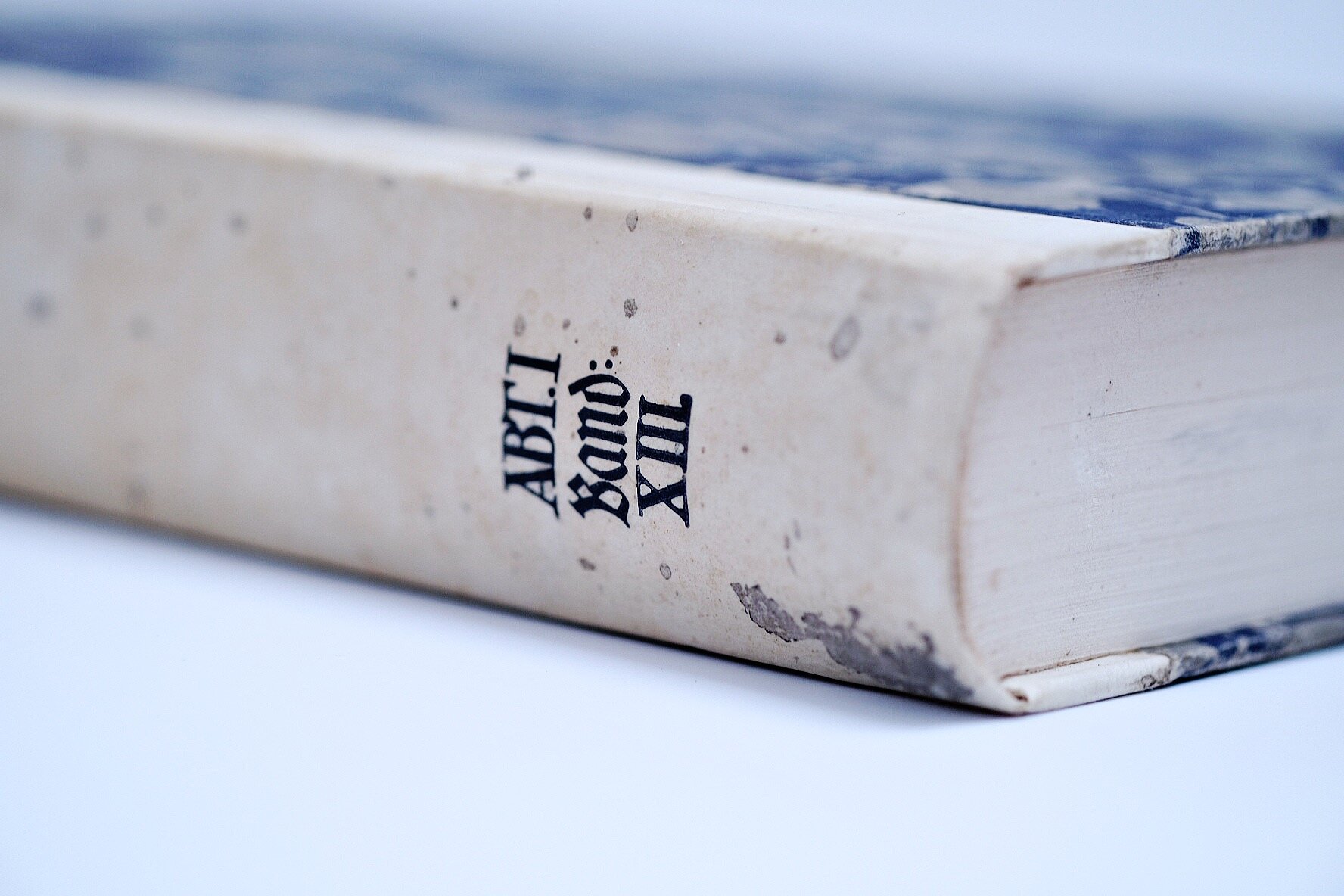

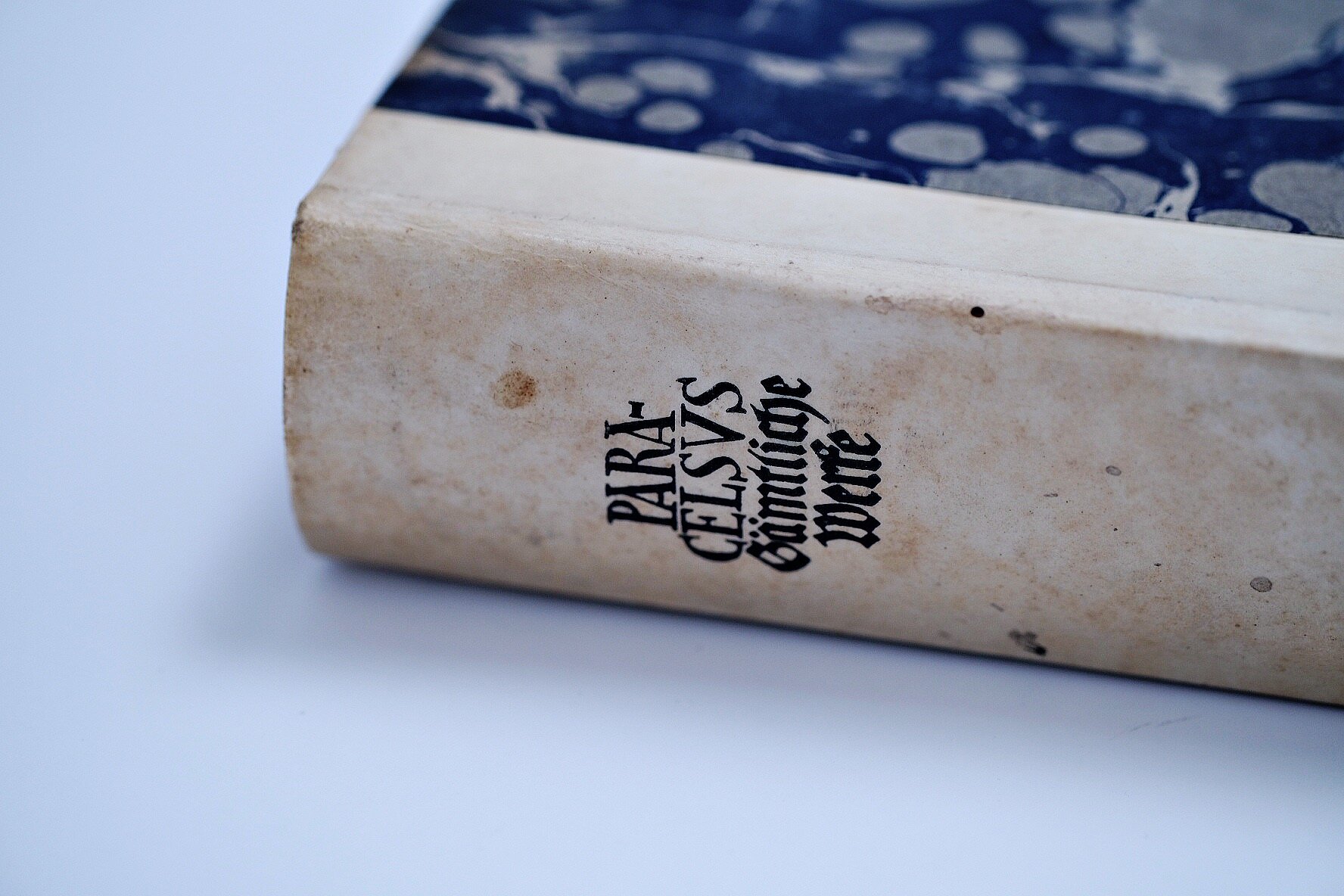

Paracelsus’s short treatise on the ‘Difference of Body and Spirit’ first appeared in print in 1572, thirty years after his death. Like several other shorter writings, it was included as an appendix to his Archidoxis magica in an early German print edition from Basel. The text forms the fourth of five short treatises, known plainly as Philosphiae tractatus quinquae. The translation provided below is a modernised version taken from the critical edition of Paracelsus’s collected writings, where it appears on pages 350-351 in volume XIII (Sudhoff, Karl von (ed); Theophrast von Hohenheim gen. Paracelsus, Band 13, München und Berlin: R. Oldenbourg Verlag, 1931).

It takes Paracelsus less than two pages to establish a critical foundation for a Western type of shamanism almost entirely forgotten or overlooked today. In sparse words and with the precision of an adept in his field, he gives us the essential outline of the ecosystem of spirits within which the magus operates and orientates themselves. Making his subject plain simple, avoiding all abstractions but rather pulling on simple everyday comparisons, Paracelsus establishes the essential dichotomy of body and spirit.

What we are presented with is a clear hierarchy of power: The spirit is being presented as the superior function, teaching, training but equally seducing the material body. Their symbiosis is wonderfully summarised in the almost offhand statement: “The body remembers, the spirit accomplishes.”

As Paracelsus expounds in the following fifth treatise in further detail, the spirit fades into the background when the body is awake and vice versa. Like two sides of a coin, like night and day, body and spirit under natural circumstances are never witnessed standing side by side, but co-inhabit the realm of creation in their own tides. – As Paracelsus explains in a later text also bound into the Basel edition of the Archidox (Liber de Imaginibus), this straight-forward setting establishes the essential challenge for the work of the mage: To enable their consciousness to temporarily shift out of its natural attachment to the body and to travel with their spirit instead. Much of the work of the mage according to Paracelsus, one could say, consists of mastering the art of crossing over thresholds that normally - and for very valid reasons - uphold separations between functions, forces and organic fields.

Essentially for Paracelsus’s complex idea of man, we do not find a value judgement assigned to the three constitutive components of body, spirit, and soul. They each do what they are supposed to, in mutual dependency, and neither could replace the function of the other. Such is the ecosystem or hive-being that is the microcosm of man. It follows, and this is the relevant point to stress, that man as such is not any more genuinely expressed in their body, their soul, or their spirit. While there is a sharp distinction in functionality, and a clear hierarchy in power, there is no hierarchy of veracity in how these functions embody the identity of a human being. The latter only exists as a microcosm of all three of them coming together in one ecosystem. Man is not their body, man is not their soul, and neither their spirit. Man is what happens when all of these are bound into a single temporal shape. Man is the endless expedition this trinity travels on together on.

All the above is expressed in just 20 lines of text.

From this introduction, Paracelsus moves on and now opens the broad vista of spirits dwelling and residing outside of man, around them, above and below them. He lists celestial, infernal, human, and the spirits of the four elements, and yet he does so in giving each of them the same terminology: “spiritus” followed by the Latin term for the species of spirit. Thus, Paracelsus again portrays a level playing field and tries to absorb any biased perception of judgement or hierarchy. While he does call out the angels as “the best spirits”, he wants his reader to see all of these creatures inhabiting the world as one, in one and the same moment. The remaining sections of the text are then dedicated to expounding on precisely this notion of uniqueness, diversity and mutual dependency of the spirits, forming one living ecosystem. Paracelsus compares the spirits to the world of workers and craftsmen: Their function is unique and portrays a skill, power, and beauty that none of their peers could fill if their work was absent. Like the tailor depends on the weaver, like the carpenter cannot cut stone and the mason doesn’t know how to work with wood, that is how each species of spirits depends on the other – including the human spirit.

When we speak of the ‘art’ in a magical context, I wish, we would begin to understand it in a more Paracelsian way: Not as a singular, but as a living compendium of ‘artes’, of crafts and skills and talents and gifts – each bestowed upon a different species of spirits. Perfecting the art that is magic, thus, for humans means not only mastering their own gifts and talent as a species of spirits. It also means to develop understanding and respect for the myriads of spirit ‘artists’ we all live surrounded by.

You would think, assuming our position in the ecosystem would be one of the most instinctual, natural things to for a magician. And yet, it seems to be one of the hardest things to accomplish these days? Maybe that is, I wonder, because we have become so obsessed (or confused?) with high and low magic, with learned and folk magic, with native cults and modern temple magic, that we no longer see the forest for the trees: We are all a weave, and nothing out of ourselves.

TRACTATUS IV. OF THE DIFFERENCE OF BODY AND SPIRIT.

There are two contrarious to each other, the body, and the spirit. For the spirit instructs the body and deceives the body in many evils and sins, and yet the body must pay for such sins, and the body may not instruct nor deceive the spirit. So the body is visible and comprehensible, but the spirit is invisible and incomprehensible. So the body sins and does evil, but the spirit does not, neither does the soul, therefore the body must pay again and not the soul or the spirit. So the body eats and drinks, but the spirit believes. The body is destructive and perishable, the spirit eternal. The body dies, but the spirit remains alive. The body is overcome by the spirit, but the spirit is not overcome by the body. The body is dull and dark, but the spirit is clear and transparent. The body becomes sick, but the spirit remains healthy. To the body everything is dark, but to the spirit the darkness is light and transparent like a crystal, therefore it can see through all mountains to the lowest ground. The body remembers, the spirit accomplishes. The body is mumia, the spirit is balm. The body is of death, the spirit of life. The body is of the earth, the spirit of heaven and of God.

So it is to be known also further that the spirits are many, and they are each one differently than the other. For there are spiritus coelestes, spiritus infernales, spiritus humani, spiritus ignis, spiritus aëris, spiritus aquae, spiritus terrae, etc.. And the spiritus coelestes are the angels and the best spirits, the spiritus infernales are the devils, the spiritus humani are the dead human spirits, the spiritus ignis are the salamanders, the spiritus of the air are the sylvani, the spiritus aquatici are the nymphs, the spiritus terrae are called the sylphs, pygmies, Schrötlein1, Büzlein2, and mountain men.

And each one has their special office and their special profession from God. And everything what is imposed to man by God his creator, may it be good or evil, that he accomplishes and carries out in his dwelling or in his chaos. For no one can intervene with the other in their office or do the other's handiwork. In the same way as among us men there are different crafts and trades: One is a carpenter, another a stonemason, a third a weaver, a fourth a tailor, a fifth a cobbler, a sixth a locksmith, etc.. And the carpenter cannot hew the stone as he hews the wood, just as the stonemason cannot do the work of the carpenter. The weaver cannot weave a skirt or trousers, but he can make the cloth for them. The rest he leaves to the tailor, who makes skirts, coats, pants, and other clothes out of it. It is the same with the shoemaker, the locksmith, and all other craftsmen.

Likewise, you should know about the spirits: That no one alone can be a carpenter, a stonemason, a weaver, a tailor, a locksmith, a shoemaker, etc. and all of it together. For although everything is possible for the spirits and they can accomplish everything, just like men and even much better, one spirit cannot do everything alone. Instead, one spirit can do this, the other that, the third something different again – and thus the spirits carry their arts together, just like we humans.

TRACTATUS IV. VON DEM UNTERSCHIED DER CORPORUM UND SPIRITUUM.

Es sind zwei sich widerwärtig [feindselig gesinnt], der Leib und der Geist. Denn der Geist unterrichtet den Leib und verführt den Leib in vielem Übel und Sünden, und muss doch der Leib solche Sünden bezahlen, und der Leib mag den Geist nicht unterrichten noch verführen. Also ist der Leib sichtbar und begreiflich, der Geist aber unsichtbar und unbegreiflich. Also sündigt der Leib und tut übel, aber der Geist nicht, auch die Seele nicht, darum muss der Leib wieder bezahlen und nicht die Seele oder der Geist. Also isst und trink der Leib, dafuer glaubt der Geist. Der Leib ist zerstörerisch und vergänglich, der Geist ewig. Der Leib stirbt ab, der Geist aber bleibt am Leben. Der Leib wird vom Geist überwunden, der Geist aber nicht vom Leib. Der Leib ist trüb und finster, der Geist aber lauter und durchsichtig. Der Leib wird krank, der Geist bleibt gesund. Dem Leib ist alles finster, dem Geist aber die Finsternis licht und durchsichtig wie ein Kristall, darum können sich durch alle Berge hindurch sehen bis auf den untersten Boden. Der Leib gedenkt, der Geist vollbringt. Der Leib ist Mumia, der Geist ist Balsam. Der Leib ist des Todes, der Geist des Lebens. Der Leib ist von der Erde, der Spiritus vom Himmel und von Gott.

So ist auch weiter zu wissen, dass der Geister vielerlei sind, und sie je einer anders als der andere sind. Denn es gibt spiritus coelestes, spiritus infernales, spiritus humani, spiritus ignis, spiritus aëris, spiritus aquae, spiritus terrae, etc.. Und die spiritus coelestes sind die Engel und die besten Geister, die spiritus infernales sind die Teufel, die spiritus humani sind die abgestorbenen Menschen Geister, die spiritus ignis sind die Salamander, die spiritus der Luft sind die Sylvani, die spiritus aquatici sind die Nymphen, die spiritus terrae sind die Sylphen, Pygmäen, Schrötlein, Büzlein, Bergmännlein genannt. Und ein jeder hat von Gott sein besonderes Amt und seinen besonderen Beruf. Und alles was ihm von Gott seinem Schöpfer, dem Menschen zu tun auferlegt ist, es sei denn Gutes oder Böses, das vollbringt und verrichtet er in seiner Wohnung oder in seinem Chaos. Denn keiner kann den anderen in seinem Amt greifen oder des anderen Handwerk treiben. Zu gleicher Weise wie unter uns Menschen unterschiedliche Handwerke und Gewerke sind: Der eine ist ein Zimmermann, der andere ein Steinmetz, der dritte ein Weber, der vierte ein Schneider, der fünfte ein Schuster, der sechste ein Schlosser, etc.. Und der Zimmermann kann den Stein nicht hauen wie das Holz, ebenso wie der Steinmetz auch nicht die Arbeit des Zimmermanns vollbringen kann. So kann der Weber keinen Rock oder keine Hose weben, aber wohl das Tuch dafuer kann er machen. Das andere überlässt er dem Schneider, der macht daraus Rock, Mantel, Hosen, und andere Kleider. Genauso ist es mit dem Schuster, dem Schlosser, und allen anderen Handwerksleuten zu verstehen.

Desgleichen sollt ihr auch wissen von den Geistern, das auch nicht einer allein ein Zimmermann, ein Steinmetz, ein Weber, ein Schneider, ein Schlosser, ein Schuster, etc. und alles miteinander sein kann. Denn obgleich den Geistern alles möglich ist und sie alles vollbringen mögen, ebenso wie die Menschen und noch viel besser, so kann doch einer zumal nicht alles miteinander. Sondern jener kann das, der andere dieses, der dritte auch ein anderes, und auf diese Weise tragen die Geister ihre Künste zusammen, gleich wie wir Menschen.

see: “Schrötlein […] schrötlein or more often schröttlein, which not infrequently occurs as a variant of schrätlein, schrätzlein and denotes a kobold: incubus ... der alp, das nachtmänlein, der schrötle” (Deutsches Wörterbuch von Jacob und Wilhelm Grimm. Lfg. 10 (1897), Bd. IX (1899), Sp. 1794, Z. 23) ↩︎

Diminutive form of old German “Butz”, a master ruling of other unruly chthonic spirits in German folk-magic and specifically related to the wild days of carnival (see: Deutsches Wörterbuch von Jacob und Wilhelm Grimm. Lfg. 3 (1855), Bd. II (1860), Sp. 588, Z. 40) ↩︎