The Role of Myth in Ritual Magic - Part 3

Writing about the Myth in Ritual Magic I often had to think of two stories I heard during my time at university. Back then I studied Intercultural Communication and discovered a lot about what each culture teaches its members and how this process works. I also learned a lot about the often highly specialized skills acquired and passed on during socialization. Many of these cultural skills are taken for granted or even assumed to be universal by its members - whereas in reality they aren't. In fact it is these skills that often shape and limit the worldview of any culture's members.

So let me share these stories with you. And let's find out together if and how they can enrich our own practical approach to ritual magic. Personally I find these the most fascinating adventures - finding something relevant in one place of life and then applying it to a completely different one. I think it is what helps us best to keep our perspectives fresh and unclouded: remaining open to discovering unfamiliar sides of the things we thought we knew so well already...

4) The Myth as Ritual Language - continued

The first of these stories was about a team of researchers spending time with a remote desert tribe in the Sahara. During their stay they asked for permission to take photos of the members of the tribe. None of the tribe's members knew what a camera or photo would be and so they agreed to stand in front of the strange black box. When the researchers showed the photo they had taken of a woman and her nephew to the woman they discovered something completely unexpected. The woman didn't recognize herself, neither did she recognize her nephew on the photo. All she saw were patterns of colors on a glossy paper. She had never learnedto see photos.

When members of the Western cultures look at a picture what goes in their brains doesn't rely on inborn qualities. Instead it relies on what we have learned. Skills like 'seeing photos' (i.e. interpreting or decoding would be more accurate terms) is a trained quality in our brains which quickly becomes automatic over time. It seems recognizing familiar shapes on a photo, processing the very idea of transforming a three-dimensional object onto a two-dimensional surface has to be learned. It is a skill we aquire during socialization and not something that comes hard-wired into our brains from birth.

Now, some of you might think it's simply a question of cultural progress? The more 'advanced' a culture the broader their mental capabilities and thus the higher their mental skill level to process seemingly abstract information. Well, unfortunately - or shall we say luckily? - this eurocentric theory has been proven wrong long ago. It's the second story that illustrates the deeply flawed way of 'progressive cultural thinking' very nicely.

A research team had learned that a small Mediterranean tribe had preserved an unknown way of navigating their ships across the ocean. Instead of using fixed stars they had heard this tribe would use certain unknown wave types which were specific to certain areas in the sea to navigate their wooden vessels. Interesting enough this way of navigating had prooven to be so reliable and accurate that they still used it today and never saw a reason to change to a more 'advanced' way of navigation. Steering their ships across the open ocean this method of navigation came cost free and allowed them to direct their ships to a specific harbor by a couple of hundred meters of accuracy...

So the research team decided to spend time with the tribe, accompany them on their trips across the Mediterranean sea and learn their way of navigation. A few days into their first trip an experienced sailor showed them the waves in question. They had to walk to the front of the ship, lean over the bow and simply watch. The problem was the researchers didn't see the any special types of waves. The tribesman pointed them out and explained they were right in front of them. Yet even after days of joint travels and intense staring into bow-waves the researchers didn't see the waves. All they saw was troubled water. Their brains simply hadn't been trained to 'decode' the image of the water surface as the brains of the tribe's men had.

Even after years I still find these stories so fascinating. There is so much they teach us about the things we use to take for granted. But what do they have to do with myth or ritual magic?

The two stories make some essential differences in the way we perceive the world plain obvious. However, they do not point at the blind spots in our ability to perceive in order to expand it. The point of the stories really isn't about getting better at perceiving. Instead they aim to show the vast possibilities life throws at us to make sense of it. The blind spots in our perception will always remain; they can only be located at different places... Once we settled on our own specific way - and we have been socialized within the norms of the tribes or the researchers - switching between these different modes of perception becomes increasingly difficult. And potentially impossible at some point.

As we have seen the above is true for actual human interactions. I.e. members of the same genetic race experiencing not only breakdown in communication but also breakdown in how they perceive and make sense of the world. Now, in magic we rarely care about communication better with other humans - but we strive to engage with members of completely different 'races'. So the question is: What of the above could teach us something about challenges in communication with spirits, demons, gods and goddesses? Are there moments when we both stare at the surface of a paper, the water in the chalice, the fire in the lamps - and perceive completely different things? And if so, then what does it take to still engage with each other in a meaningful way?

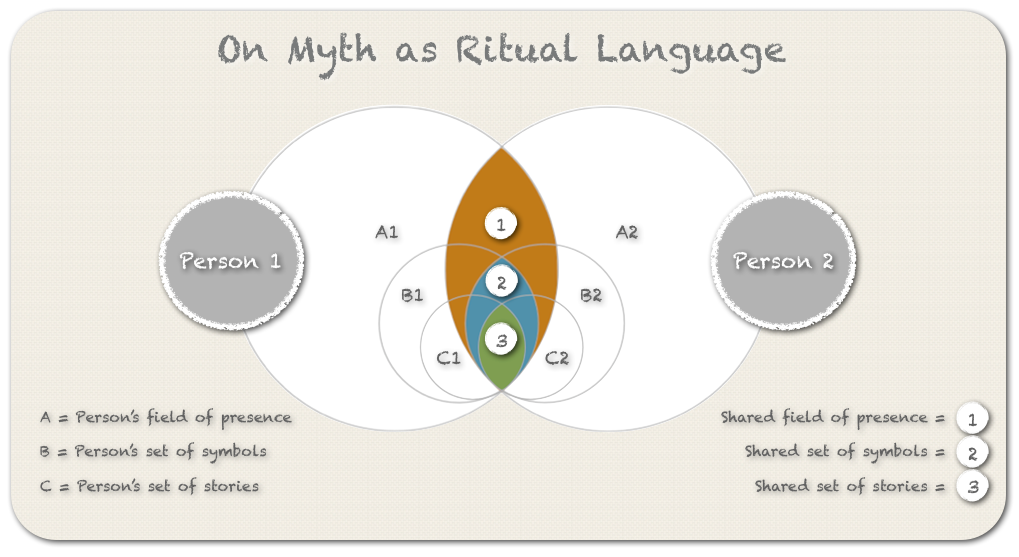

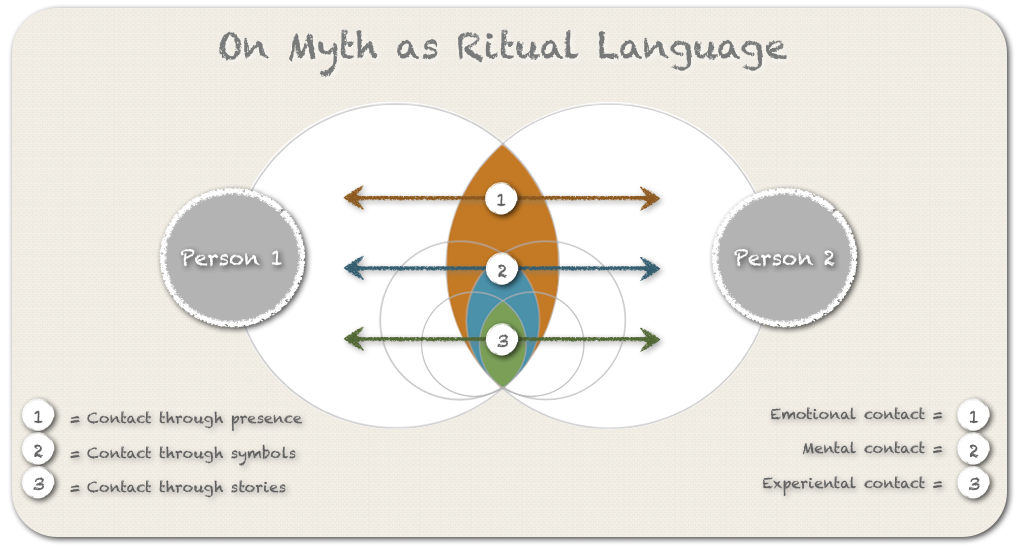

If we leverage a basic communication model things become rather simple and obvious. In order to engage in any sort of functional communication with a human or spiritual life form we have to ensure there are few things both communicators share. The three most basic necessities for functional communication are: (1) a shared field of presence, (2) a shared set of symbols and (3) a shared set of stories to relate to.

- Shared field of presence: The first one is quite simple: communicating with someone who isn't around - may it be physically or virtually - is impossible. That is if we exclude all sorts of inner monologues to an imagined other. It's a field of shared presence that needs to connect both communicators.

- Shared set of symbols: The second criteria is normally determined as a shared language. I.e. any set of symbols or code that the two beings involved can rely on to communicate. This set of symbols is used to express information (encode messages) and ensure the same information is understood with an acceptable level of noise and loss in between by the other being (decode messages).

- Shared set of stories: The third component is a shared reference frame to convert information into meaning. Such a set of shared stories can both be held consciously and unconsciously by the communicators. Normally it represents a large part of the collective memory of any given group. By relating to these stories in their own communication group identity is reconfirmed, historic coherence and continuity is ensured and the group myth are kept alive.

Here are a three slides that explain this process in very simple terms:

If you have made it to this point we have quite a ride behind us. We have stolen insights from anthropology, communication science and linguistic to understand what it takes to create meaningful communication. Let's bring these insights back into the context of ritual magic.

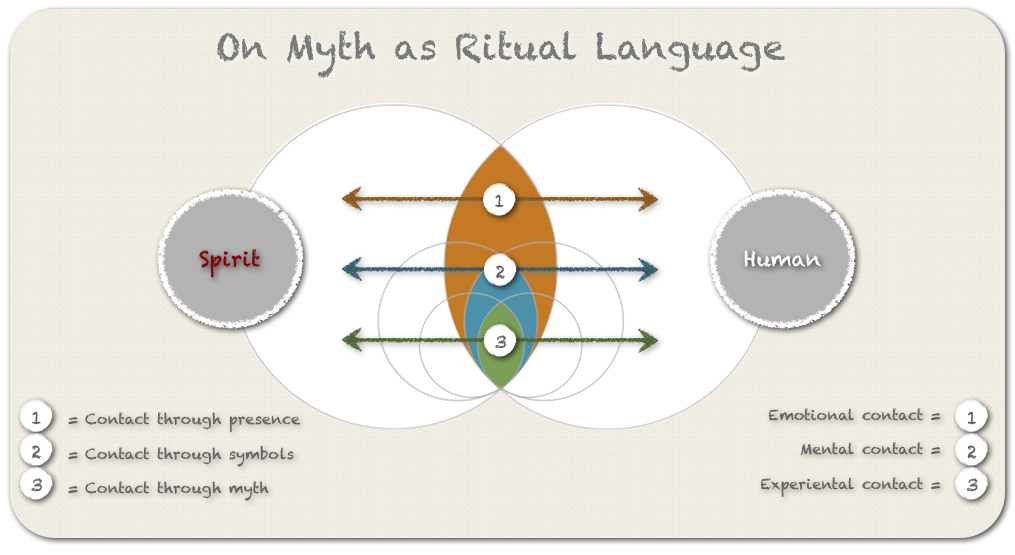

In a previous chapter we have spoken about the function of Myth in Ritual Magic. The stories of the myth are the patterns established between spirits and humans that allow for mutual interaction. They are actually shared stories written from 'both sides of the mirror'. I.e. spirits and humans have contributed to the creation of the myth alike, both of them have their fingerprints, their thoughts, their minds and blood in it.

So in our interactions with spirits the myth can be regarded as the central core of the model above - where all three circles overlap. It's the shared space between us and the spirits, the place where we share a field of presence, a common set of symbols and a deeply arcane set of stories that unites our races. It is what we can rely upon in our interactions with spirits to make sense both on the outer and the inner realms. It is a story spoken in a language that both can be understood by spirits and humans alike.

Think of a dream. You are standing in front of a mirror. Your reflection on the other side, however, has turned into a different gestalt. Your reflection has taken the shape of your familiar spirit or maybe the goddess you are devoted to. As you move in front of the mirror, her movements answer to yours. As she raises her arms to greet you, so do yours in reply. And as she speaks to you, so your mind derives meaning. As you speak to her, so she derives intent. The myth is what establishes this field of mutual understanding. The myth is the very thin slice of dream glass in between you. It's the window between worlds.

At the same time the myth is nothing but a story. What I am describing above is something living, like a heart pumping warm blood into a relationship between two beings. How you transform words from a book into a living mirror that's what I want to explore with you in a another post. It will be very playful though, like every good story is.

"The 'image' does not represent the 'object' - it becomes the object. The former does not substitute the latter, but it contains the same powers as the object itself, thus replacing it in its immidiate presence." (Ernst Cassirer)